//www.googletagmanager.com/ns.html?id=GTM-5DBTHW

(function(w,d,s,l,i){w[l]=w[l]||[];w[l].push({‘gtm.start’:

new Date().getTime(),event:’gtm.js’});var f=d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0],

j=d.createElement(s),dl=l!=’dataLayer’?’&l=’+l:”;j.async=true;j.src=

‘//www.googletagmanager.com/gtm.js?id=’+i+dl;f.parentNode.insertBefore(j,f);

})(window,document,’script’,’dataLayer’,’GTM-5DBTHW’);

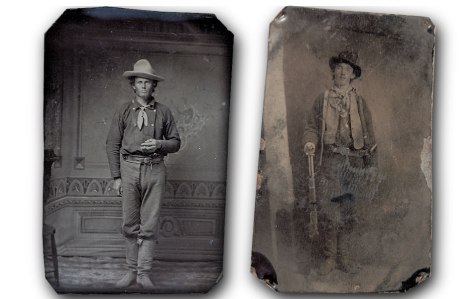

Billie the Kid-the hero of Aaron Copland’s 1938 American “populist” ballet conformed to the idea Americans had of him; established by the MGM film, released in 1930. It was previewed by audiences with Billie being shot at the end. The audience was not pleased. Why? Wasn’t Billie a murdering outlaw?

Yes, and no. It pained those merciful audiences enough to demand a romantic ending. People often forget that art is supposed to be entertaining and that can mean different things at different times in history. Art only has the meaning at its inception which is appropriate to the audiences of its days.

Billie the Kid worked its magic in a patriotic way, helped along with its publicity of Billie heroically assisting the poor and downtrodden by relieving the banks and wealthy landowners of the money or property they had “stolen.” John Dillinger, portrayed much in the same way, also became an icon for the preservation of American values and hard-earned independence, but we do not see a ballet about him.

Billie the Kid was a familiar hero and ballet was art appreciated at this time for different themes and representing different values than would have been presented even ten years later. One could hardly romanticize John Dillinger in an American folkloric ballet in say the 1950’s or 60’s as his memory was too fresh in the public’s mind. We could not see him as a ballet dancer.

Waging a war against tyrannical villains, the Kids violence was justified by his chivalric code. He came to become associated with an idea of individualism that was thought to be disappearing in America. Ballets usually must start with a fairy tale, not a fact, a romantic figure, not a soldier of fortune, or so it once was thought. What connotes the heroes in ballet? The villians? Must they all be fantastical creatures or can they be real men, not sorcerers and fairies?

The ballet in 1938, and the film, were each preceded by journalist Walter Burns book (in 1926) which was a fantasized version of the life of Billie the Kid, imagined by him after a trip to New Mexico (The Land of Enchantment) where he heard stories of the Kid which changed his opinion of a character he always believed to be a hardened criminal. The Saga of Billie the Kid became a bestseller, as escapist literature, hinging on the oppression of poverty, rise of fascism in Europe, as well as the collapse of the stock market in 1929. He used interviews with people who had known Billie to write his book, which redefined the man-myth into one of heroic popular culture.

Though Copland’s ballet is a mere fifteen minutes long, Billie’s life was also a mere twenty years long when he was shot and killed by Pat Garrett in 1881. Public sympathy most certainly took into account his youth, as it was thought that a kid might have a tumultuous youth, and an hour of redemption, in which to repent on the error of his ways, and which this legend never got, thus making him an anti-hero, but one whom is cheated of his chance of salvation. He was soon forgotten at the time because he exemplified the epitomy of the lawlessness of the American west, was purported to be a cold-hearted killer by lawmen cleaning up the territory, which also served some political purpose it is believed. He was the “devil’s meat” according to one account. By the early 1900’s his tale was beginning to be forgotten, as his actions were the types with which we tend to disassociate; that is, until Burns’ book came along allowing Americans to re-envision the life of Billie the Kid. Popular westerns filled the shelves of bookstores.

It is not the first time, and probably not the last; we will make a hero of a devil. But it may be the last time we count flaws as more interesting than perfection, if we are not careful. This, in part, explains why Copland chose to construct a hero fable based the life of a man of dubious heroic qualities, upon which to base his ballet. He elected to demonstrate how bad could be converted into good, and somehow managed to fill a need of American theater-goers to raise a hero from the ashes. A man of steel. Copland felt that the Kid was inspirational, wrongly accused, and as well gave Americans a new lease on the life of accessible American culture by revitalizing its history. This had broad appeal and came to be a popular theme of contemporary ballet and musicals, such as the works of Jerome Robbins, including West Side Story.

Even today, an artist such as Sergei Polunin, may find a way to be the director of his own career through the natural acceptance and appeal of this device. We rebel. We rebel against what we feel is unjust and what is wrong, unless we are inhuman and unnatural, robots. Robots cannot really be artists-can they? Character is much different from discipline. This was our own Golden Age of ballet, popularly headed by Russian, George Balanchine, and it is unusual that at its core are stories that esteem the American west, gunfighters, murderers, gangsters, soldiers, troubled youth, and such characters that are not in possession of some of the characteristics of traditional heroes, do some bad things, and somehow we continue to love the bad boys and girls of our culture, the misguided, the downtrodden and especially those that nobly champion those values which we would if we could. The truth is you cannot really have one without the other for at times everybody needs an anti-hero.

Copland, having studied abroad, came home determined to give Americans music that was “as recognizably American as Mussorgsky and Stravinsky were Russian.” Through his use of tone clusters and dissonance, both modern music, Copland produced something which sounded American, but also offended. Much in the way an anti-hero might offend and yet be reconciled to our good graces, or to whom we might even relate in fiction, if we dare. It would never really achieve a vast audience due to the fact that most people dislike dissonance in modern compositions. A new study proposes that in fact we prefer consonant chords for a different reason, connected to the mathematical relationship between the many different frequencies that make up the sound.

Some people just naturally prefer consonance over dissonance. What they really require is harmonicity- and like so many things in art and life, what this boils down to is math.

However, interested persons can read this little explanation of the the music here:

http://www.nytimes.com/books/99/03/14/specials/copland-modernist.html

and can listen to the full ballet here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrD36k8Sn2k

and see a bit of the ballet from labnotation (Eugene Loring) here: